NOTE: This page is still a work in progress, please feel free to share any remarks, photos, or stories about Jay with Communications Specialist McKenzie Meza (mim4@arizona.edu(link sends e-mail))

Dr. Jay Quade

Professor

Geochemistry

Deceased October 17th, 2025

Expertise Jay received a B.S. in Geology at the University of New Mexico in 1978, and went on to obtain his M.S. (1981) and Ph.D. (1990) in Geology at the Universities of Arizona and Utah, respectively. Quade joined the faculty in the Department of Geosciences at Arizona in 1992, and has been a Full Professor there since 2003. His interests are in low-temperature geochemistry and paleoenvironmental reconstruction. He has worked all over the world documenting the evolution of climate and landscapes over the past 60 million years, including the context of early hominids in Africa. Quade is has participated in >160 scientific papers, 45 of them as a first author, since 1986. He has received many awards including the Farouk El Baz Award, GSA (2001); GSA Fellow (2015), AGU Fellow (2015), Ben Tor Award from Hebrew University (2014), Geochemical Society Fellow (2017); Arthur L. Day Medal (GSA) (2018), and U.S. National Academy of Sciences (2024)

Please find below a beautiful GSA memorial to Jay put together by Julio Betancourt, Thure Cerling, Peter DeCelles, and David Dettman.

From Department Head Professor Paul Kapp:

"It is with profound sadness that I share the loss of Professor Jay Quade, member of the National Academy of Sciences. Jay passed this morning after battling Parkinson’s disease. Jay was a real-life Indiana Jones who inspired and elevated all around him. His insatiable passion for discovery—in both the field and lab—made him one of the most influential geoscientists of his generation. He was an exemplary teacher in lower and upper division courses and devoted countless months to teaching summer field camp. Jay was a warm and thoughtful colleague, mentor, and friend. His big smile, infectious enthusiasm, and optimism brightened every room. His wisdom and kindness touched countless lives, and his loss will be deeply felt throughout our community."

Pictured Right: Jay Quade in Nepal, 1996

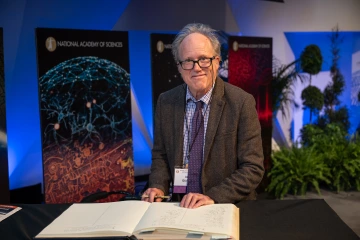

Pictured Below: Jay being inducted into the National Academy of Science

This is a big loss for the Department of Geosciences. With nearly 400 publications, and almost 30,000 citations, Jay has had an extremely influential career. As a 3rd generation geologist, his awards and accolades are nothing short of impressive. Most notably, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in Spring of 2024. Prior to being elected to the National Academy of Sciences, Jay earned the Arthur L. Day Medal in 2018 from the Geological Society of America for "outstanding distinction in contributing to geologic knowledge through the application of physics and chemistry to the solution of geologic problems."

Memories from colleagues and friends of Jay:

Tribute to Jay from Naomi Levin, University of Michigan:

From April 2005 to April 2006, I had the privilege of being a visiting scholar in the Department of Geosciences at the University of Arizona, where I was hosted by Professor Quade. The last time I met him in person was during his visit to Beijing in June 2006. We remained in contact through email, with our final exchange taking place in June 2024. In that message, he mentioned serving on the advisory board for the journal Quaternary Research and sought my thoughts on its future direction. It’s difficult to comprehend that he is no longer with us. His dedication and kindness will always be remembered, and the time I spent with him in Tucson remains a cherished memory. - Shiling Yang, Insitute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences

From Professor Peter DeCelles:

Image

Grad student Tshering Lama Sherpa (middle) and one of our Nepalese helpers | Image

At a landslide that blocked the road, waiting for it to be cleared |

Jay was such a huge influence on my time at the U of A. I’ll never forget field camp back in 2003, picking up dinosaur bones with him and his son in the Morrison Formation in Utah. I also remember his Quaternary Geochronology class and wondering how much further my brain could stretch on such a complex subject. I always loved the stories he shared about his archaeological adventures in Africa and those early days prospecting for gold in Alaska—hiking up river channels looking for the sources of placer deposits. Every young geologist’s dream job…! He was one of a kind, and his teachings will never be forgotten. - York Lewis, B.S. Geoscience, 2024

Jay was a beacon to me for more than 20 years. Personally, and professionally. I learned so much from him and loved being with him, whether in the field or in a coffee shop. Its difficult to imagine this world without him. Our collaboration started in 2004 when he invited me to work with him in the Atacama Desert. Since then, we worked together in several deserts in the world. Jay spent several months at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. During that time we developed the ideas that are currently at the base of our mutual research project, in which we also have been sharing the supervision of PhD student. In 2023-2024 I was was lucky to spend a 6 month sabbatical with Jay in Tucson. Below are several photos of Jay and other researches. Jay left us a legacy of curiosity, inquisitiveness, and awe of the world around us. Scores of students, including me, now positioned all over the world, will remember him and will spread his spirit. - Ari Matmon, Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Image

| Image

|

Image

| Image

|

I used to work as a graduate student for Paul's Suture Zone project with Peter Lippert and Guillaume Dupont-Nivet and that was the time I got to know Jay. I moved to Tucson as a postdoc from 2015 to 2017, and got to know Jay better. We had collaboration even after I moved to Rochester in 2017 and back to China in 2021. When I was visiting Tucson in November 2023, I had a meeting with Jay at the lunch time and we talked about the hydrothermal events that I identified in the Himalayan rocks with the help of the carbonate clumped isotope data acquired in his lab. I was surprised at that time that Jay was not in good health as he was in 2017 when I moved away to Rochester. I thought that his Parkinson’s disease was stable and in good control. I did expect things were going worse so quickly.

The first time when I met Jay in 2011 in the field, he told me that the a critical section that we studied to constrain the palelatitude of Eurasia southern margin was afected by hydrothermal alteration. Proving this and correlating it to remagnetization of these rocks took us lots of effort, and that was the most important part of my PhD and Postdoc projects which Jay contributed significantly.

Jay is a great person to be a friend and mentor, I feel lucky to have known and worked with him. Please take my deepest condolences to his family. I have been and will always by inspired by his kindness in personality and passion in geology. Below are some photos in Tibet in 2011 when I first met Jay. He was healthy, strong and nice to everyone as always. May Jay rest in peace and no sickness in heaven. - Wentao Huang from the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research

Image

| Image

| Image

|

Image

| Image

| ← Photos shared by another colleague, Shun Li. |

I was Jay Quade's graduate student from 2011 to 2015. I'm super sad to hear of his passing. He was a great and beloved mentor to me. Probably the greatest boon is that at one point in grad school Jay asked me to scan some black and white photos of his days running track at University of New Mexico when he was in college. - Adam Hudson

Image

| Image

| Image

| Image

|

Jay has been my greatest teacher and mentor, and an invaluable friend. He is the scientist who had the most profound influence on the way I practice science today. Not a week goes by without me thinking of him.

I was still a young and inexperienced French PhD student when I asked Jay to be part of my dissertation committee in France. To my surprise, he responded quickly and positively, and even flew all the way to Poitiers for the defense in 2013. When I asked if he would host me at UA for a one-year postdoc, he accepted without hesitation. Just a few days after my arrival, Jay drove me out to Pahrump, Nevada. It was the second town in the US I had been after Tucson, and it was both an amazing fieldtrip and a cultural shock. He knew every single arroyo, outcrop, and countless stories about weird guys he encountered during his years of fieldwork in the area. On the way back, we decided to go off the beaten path, he had me plant my tent on icy ground somewhere in northern Arizona, it was the middle of January. The full wild west package in less than a week.

During my year at UA, we spent days and days scouting southern Arizona sedimentary basins for suitable outcrops – officially for a paleoaltimetry study, but unofficially just to be out in the field, climbing remote mountains and investigating odd spots on the geological map. I remember the countless fire camp stories he would tell us in the evening. The forgotten crashed plane in the forest, his PhD years living with his wife and kids in a van in the middle of Nevada, the dead body in the middle of the desert, or the time he left his sherpas behind to climb a >7000 m mountain in Tibet. I remember that he was an incredibly fast hiker, always ahead of anyone while we were out in the field. Keeping pace with him was a real challenge. His daily runs up the stairs in Gould Simpson (twice per day, and eight times at the end of the week, if I recall correctly) significantly contributed to build his reputation of physical powerhouse. We brought one of his prospective master’s students for one afternoon of fieldwork in the Tucson Mountains, and we ended up stuck in a forest of jumping and teddy bear Chollas, with both of us having multiple cholla stems stuck to herself; in the meantime, he was hopping from rock to rock, untouched by the cacti. Only once I manage to outpace him during a field day, and it was no small victory for me (I can even tell that it happened in the Chiracahua Mountains). I don’t think I’ve ever seen him tired after a day of work.

I sometimes wonder if there is a place or a geological basin Jay hasn’t touched, because every time I start a new project, I discover afterward that he has already worked nearby or on a similar topic. He probably passed on to me his fascination with the same geological features, and I now find myself drawn to the same regions and research topics that captivated him. It’s actually quite a challenge, because his scientific papers always set the bar so high, forcing me to rethink everything I write or do, just to make sure I can keep up with his previous work.

It goes without saying that I learned a lot with him during my short stay in Tucson. But it’s not the science I cherish and remember the most: it’s these times when we went looking for scorpions under the moonlight, the lunch breaks in the basement of Gould Simpson (the big and dark place where Adam Hudson, he and I were the only occupants) when we would discuss about foreign politics and ancient history, or the unusual things he’d cook over the fire pit and have us taste for dinner (he introduced me to s’mores), and all the little moments that made my life in Arizona so rich and so much fun.

We stayed in touch over the years and continued to meet regularly until I moved back to France in 2020. I have been saying many times that if I ever move back to the US, it would be in Arizona, and that’s because of him. Jay’s impact on me is beyond measure and it has already been passed on to the next generation of students. And yes: I try to outrun them in the wilderness, make them camp in impossible places, and tell them wonderful campfire stories, some of which feature Jay, the crazy American geologist. - Alexis Licht

Here is one of my favorite "aha!" moments with Jay collaborating in the Atacama. We were close colleagues and friends for more than 40 years.

Jay Quade is truly outstanding in the field, where his many colleagues and students across multiple disciplines rely on his acumen, and often scurry after him for fear of missing seminal discoveries. Here’s my favorite anecdote about working with Jay in the field. In 2004, Jay and I were sampling soils every 350 m in elevation from sea level to 4500 m in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile. Our ~200-km transect crossed large expanses with and without vegetation, the latter regarded Absolute Desert. One of the questions we had was whether plants had ever invaded Absolute Desert. We decided to test this by analyzing carbon isotopes from soil carbonate. If the isotopic content of the carbonate was in equilibrium with the atmosphere, basically around -8‰, the answer is no. However, if the isotopic signature of the soil carbonate mirrored that of C4, CAM, or C3 plants, specific areas in the Absolute Desert must have been vegetated at some time in the past. As we traversed the transect, often driving cross-country in the Atacama, we (Jay) made the following discovery. Soils in currently vegetated areas along the Pacific coast, supported by fog, contained carbonate. The same held true in the sparse shrublands and grasslands at the highest elevations. Expanses without carbonate included intervening and rainless areas of Absolute Desert, and areas above 4500 m, the present cold limit of vascular plants. Sampling a soil pit in the Absolute Desert, we had the following conversation.

Jay: “Julio, I think our hypothesis was totally wrong.”

Julio: “No soil carbonates again?”

Jay: “Yeah. You actually need plant root respiration to build soil carbonates. There are no soil carbonates here because there are no plants.”

Julio: “I think I know where you’re going, Jay”

Jay: “Soil carbonate is the chemical signature of plants on Earth. When we get home, we’ll survey the literature for the first defensible calcretes in the geologic record.”

Julio: “Has to be after the Silurian with the origin of land plants, right?”

Jay: “That’s right.”

Our conversation the rest of that day ranged far and wide, from the impact of pedogenic carbonates on atmospheric CO2 levels throughout geologic history to the possible meaning of carbonates found on Mars. For me, collaborating with Jay in the field was a gift from heaven. - Julio Betancourt, Scientist Emeritus, USGS, Reston, VA

I collaborated with Jay on research in the Atacama Desert in Chile from about 2012 to 2019. Research collaborations with Jay were so rewarding due to his infectious enthusiasm, insightfulness, and keen intellect. His loss is a loss for all of us. Here are a few photos of time spent together conducting research in the Atacama Desert in Chile. - Julie Neilson, Research Professor Emerita of Environmental Science, University of Arizona

Image

| Image

| Image

|

Image

Making sparks | Image

Checking out the Carbonates | Image

Getting to the bottom of it with Jordan Abell | Image

Warming up |

Below is my tribute to Jay Quade, which I circulated in Anthropology to our Anthropology students, faculty, affiliates and friends. I know that this would be just one of many written in celebration of Jay's life, but it relates to his interdisciplinary nature and the tremendous appreciation that we have for him. Jay and I were close colleagues and friends throughout his time at UA, and he did a great deal for Anthropology at many levels as well.

Image

Tabernacle Hill, UT - 1993 | Image

Jay and Emeric just below White Mountain Peak, CA - about 3800 m altitude (about 12,500 ft). | Image

Jay just below White Mountain Peak, CA - about 3800 m altitude (about 12,500 ft). |

One memory I’ll always cherish is when Jay, Andy Cohen, and a few of our colleagues went to sample the Verde Formation near Clarkdale, AZ, in September 2022. I took my then 10-year-old son with me. At the outcrop, Jay asked Zander if he had ever looked at carbonates through a hand lens, then invited him to give it a try. He showed him how to safely crack open a sample and look for specific fabrics. After that, my son happily whaled on rocks and searched for clues with Jay’s lens for a solid hour. I got a big smile out of that — and with Jay, the whole thing happened effortlessly. - Brian Gootee, AGS

Several of us were fortunate to meet Jay Quade in 1978 at Indiana University’s field camp in the Tobacco Root Mountains, Montana. Even then it was crystal clear that Jay was an amazing individual – a rare combination of insatiable curiosity, endless energy and vast knowledge bundled in a fun-loving, humble conversationalist. Long challenging walks and many engaging discussions were memorable. Jay was an influential role model for many of us at field camp and continued to be an inspiration throughout his exemplary career. His ability to be scientifically thoughtful, open-minded, and rigorous while being generous and accepting was a defining characteristic from the field camp days through to meetings for coffee in recent years. Jay did amazing things for many people over his career; we have lost a valuable colleague way too early. - Bill McClelland, Professor Emeritus, University of Iowa

Pictured: Jay Quade and Bill McClelland at Logan Pass, Glacier National Park on a 1978 field trip during field camp. Photo by Jane Gilotti

I’m so sorry, Jay was one of the great ones and he will be sorely missed. I really thought, and wished, he would have more time with us. Here is a collection of student recommendations that were submitted for a Graduate Teaching and Advising Award that Jay won (of course he did!), it is filled with student memories and indications of what an amazing teacher and mentor Jay was to many. I’ve also included a satirical magazine cover I made for the same event. I’m grateful I shared these with Jay earlier this year. It's not an exaggeration to say that I wouldn’t be where or who I am today without Jay’s mentorship and friendship. He was wonderful, kind-hearted, funny and smart as and he will be missed. - Nathan B. English

Image

Jay at a standoff with kids in Nepal | Image

Jay in Nepal | Image

Jay getting directions | Image

Jay on the Tarai | Image

Jay and Pete Kaminsky and porters |

Image

Jay titrating on the Seti River | Image

"Which trail is fastest?" | Image

Jay crossing the Seti River

| Image

Jay the one sock wonder! |

Image

Jay sampling paleosol carbonates at Puerta de Corral Quemado, NW Argentina, January 1994 | Image

Jay checking out plant facilitation in the Monte Desert, NW Argentina, January 1994 | Image

Jay and Barbra Quade sampling in NW Argentina, January 1994 | Image

Jay, Claudio and Don Victor Pérez (middle), owner of the estancia at Puerta de Corral Quemado, January 1993 |

Image

Jay feeling at home at Puerta de Corral Quemado, NW Argentina, January 1994 | Image

Jay checking out soil exposures, NW Argentina, January 1994 | Image

Jay’s car wreck, Paso de San Francisco, Chile, January 1994 | Image

Jay looking for (and finding) rodent middens in the Atacama Desert, Chile |

In 2010 and 2011 I had the great good fortune of spending time with Jay in Tibet. Although I had known him for some time previously, it wasn’t until 2010 during our first period of “forced association” that I fully realized the depth and breadth of Jay’s knowledge and his intuition as a scientist. I will always appreciate how much I learned from Jay simply by working alongside him in the field…and during the endless days spent with him in a Toyota Landcruiser discussing matters ranging from the sublime to the ridiculous. Thank you, Jay! Fare thee well! - John Olsen, University of Arizona School of Anthropology

Image

Jay and drivers exhausted at lunch in Tibet, 2010 | Image

Jay at Neolithic archaeological site in Tibet, 2010 | Image

Jay at Neolithic archaeological site in Tibet, 2010 | Image

Jay resting, Rinqin Xibco, Tibet, 2010 |

I had the great pleasure and privilege of knowing Jay from the age of 7 until his passing. He was like a brother to me, and although we are approximately the same age, I have always looked up to him as a person with superior intellectual capacity and unassailable integrity. More importantly, even in our miss-spent youth, Jay treated others (almost all of whom were his inferior in one way or another) with compassion and kindness.

When we were in grade school, I never had to read much about ancient history, archeology, or geology because Jay had already done the research and was a veritable font of knowledge. He was already a good teacher by the age of 10!

One anecdote that shows not only how Jay sometimes conveyed knowledge in a (somewhat) practical way while also having fun at the same time occurred in the 6th grade at Huffaker Elementary school in Reno. Jay was studying Roman history (on the side) and decided it would be a good idea to re-enact a battle between the Romans and the barbarians. I don’t think he had a specific battle in mind, but with my feeble assistance we somehow convinced the entire 5th grade to portray the barbarians while the 6th grade took on the role of legionnaires. At recess, we lined up on opposite sides of the playground and the battle commenced. I’m fairly sure that it rapidly devolved into an undisciplined battle of barbarians against barbarians, but what I know for a fact is that the school principal soon came out to observe. I think he was impressed with Jay’s teaching technique and even though our weapons were imaginary and all injuries were minor, still decided that a truce was in order and that the battle should never be repeated while he was principal of the school. It never was, but I’m still grateful to Jay for making that particular school day so memorable.

Jay and I shared a love of family, friends, music (Jay was at one time a competent violinist and I still dabble at cello), humor, history, and science. I consider myself very lucky to have known Jay and believe that he made the world a much better place. - Peter Lenz

Image

| Image

Angel Lake 2015 | Image

Jay Quade E. Humboldt Range 2015 |

Image

Jay Quade E. Humboldt Range 2015 | Image

Jay Quade E. Humboldt Range 2015 | Image

Steele Lake 2015 |

I had the great pleasure of meeting Jay during the 2018 Gona field season in the Afar, Ethiopia. Leading up to 2018, I had worked with the Gona archaeological team for three years measuring section. Over lunch and dinner, epic stories were recounted of Jay mapping the Busidima Formation in his Teva sandals while only having a few grapefruit for lunch. Of course, never having met Jay I just assumed the stories were exaggerated. As one can see from reading this Memoriam page, that couldn’t be further from the truth.

I vividly recall getting ready for our first field day in 2018. Jay emerged from his tent and walked over to me in his Teva sandals to show me his extremely old/turn of the century Brunton compass handed down to him that he had been using to measure section. I found this fascinating, however I couldn’t help but to recall all those Teva sandal stories and so I glanced down at his feet and asked him, “you are going to map in those?!” He smiled and eagerly explained the how/why he switched over to sandals – to eliminate blistering. At this point I knew I was in for a memorable field campaign. Ten minutes later as we made our way to the Landcruiser, I watched from a distance as Jay scurried over to the supply tent only to reappear thirty seconds later with two grapefruits in hand. Jay spotted me, walked up to me and professed that he doesn’t like to take lunch in the field (only makes you thirsty) and prefers to just eat a few

grapefruit. And so began my epic adventures into the Busidima Formation with Jay Quade. Although those moments and the ones that followed were far too short, I learned so much from Jay and I count myself as one of the lucky ones to have crossed paths with such an amazing scientist and all-around great guy.

Pictured are Jay during the 2018 field campaign at Gona, Ethiopia, reuniting with local Afar guide, Asa Hamet. Asa Hamet was right by Jay’s side for much of his earlier geologic mapping efforts at Gona (1990s-2006). - Gary E. Stinchcomb, University of Memphis